Have you ever had to express a theory of change to convince funders that there’s a logical argument behind your innovation? Funders expect that data will be collected to evaluate whether innovations are meeting their goals. The goals should be tied to the innovation’s theory of change.

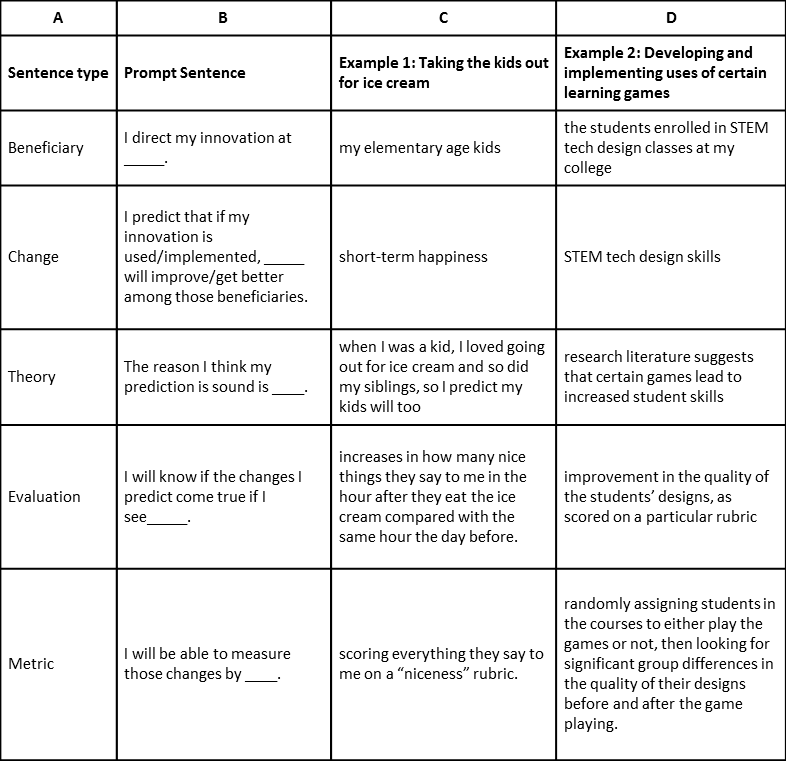

This type of thinking is very abstract, so the more you apply the abstractions to concrete situations, the clearer it will be. A useful exercise is to complete some sentences about your STEM education innovation. But first, try the same exercise for something that’s less intellectually challenging. In the table below, Columns C and D show examples of both. The sentence prompts are in Column B.

Of course, theories of change and the evaluation strategies that arise from them can get very complicated quickly. For example, let’s say you’re writing a “proposal” to your best friend, who happens to like your kids and is ready to pay for their ice cream if he’s convinced that it will make them happy. Yet, your friend is the skeptical type. He argues, “Why just analyze what they say twice? Wouldn’t it help if you also did it the day after to see if they revert back to their usual remarks? Also, what if the kids simply decide to say fewer things after they eat the ice cream? How would you interpret fewer statements rather than nicer statements? Wouldn’t it be better to simply ask them to report how happy they are on a scale or tell them that they have to make at least four remarks or they’ll only get one scoop next time?”

In the second case provided in the table, let’s say your friend expresses concern about the random assignment. “What if the students won’t like being randomly assigned?” he says. Are there other ways you could get legitimate comparison data from which to draw conclusions? How about getting a participant group by asking for volunteers, then using a design task pretest to see how they match up with those who didn’t volunteer? Then, when analyzing the post task, you could limit your comparisons to groups of participants and nonparticipants to those whose designs on the pre-task were about the same quality.

In closing, it’s helpful to think of theory of change generation as an exercise in reflecting on and expressing the logic behind your innovation’s value. But first, do it around something ordinary, like getting more exercise, and be prepared for those tough questions!

Except where noted, all content on this website is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

EvaluATE is supported by the National Science Foundation under grant number 2332143. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed on this site are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation.

EvaluATE is supported by the National Science Foundation under grant number 2332143. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed on this site are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation.